TARGET2: scale of invisible Eurozone liabilities demands action by global financial regulators

Published on 12 December 2021

We recently had a blog published by Politeia about the lack of transparency in the accounting for the debts of EU/Eurozone member states. The member states’ contingent liability to backstop the debts of the EU is an example. Member states also have a contingent liability to backstop their central banks, whose debts should be included in the ‘General government gross debt’ of these members states, as recorded by Eurostat. Two eventualities escape inclusion. Firstly where the central bank’s risk is itself a contingent liability: the risk of its having to recapitalise the European Central Bank (ECB) should the ECB incur losses on its operations, which are expanding in both quantity and risk. Secondly where the central bank’s debt is concealed, as it is in TARGET2.

What is the trigger for raising these concerns?

We have identified ten areas of contingent liabilities for member states where the underlying debt does not appear in ‘General government gross debt’. These invisible debts are rising, notably by the EU planning to borrow €750 billion by 2027 under its NextGenerationEU programme.

The visible debts of the Eurozone member states have already risen – to €11.1 trillion at the end of 2020, which was 97.3% of Eurozone GDP of €11.4 trillion.

The Eurosystem’s aggregate balance sheet, at the end of October this year, had risen to €12 trillion.

The degree of offset between the Eurosystem’s balance sheet and the visible and invisible member state debts is opaque.

That is not good enough for a matter of importance to global financial stability.

What is on the Eurosystem balance sheet?

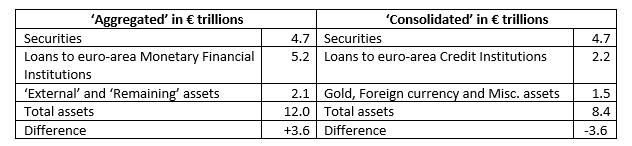

In fact the Eurosystem issues three different balance sheets. The ones on which this analysis is based are the weekly ‘Consolidated’ one of 29 October 2021 and the monthly ‘Aggregated’ one for October. The assets can be simplified as follows:

98% of the securities are the balances in the ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme of €1.5 trillion and its Asset Purchase Programmes of €3.1 trillion.

The ‘Loans to euro-area Credit Institutions’ in the ‘Consolidated’ one are the €2.2 trillion of unsecured loans to banks under Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations.

The equivalent posting in the ‘Aggregate’ one is ‘Loans to euro-area Monetary Financial Institutions’; at €5.2 trillion it is €3 trillion higher. Credit Institutions are one type of Monetary Financial Institution; central banks are the other. The accounting treatment indicates €3 trillion of loans amongst members of the Eurosystem, but where the net balance is zero: for every borrower position at one Eurosystem member, there is an equal and opposite depositor position at another. That is TARGET2.

Why is this a problem?

€3 trillion of loans in TARGET2 is more than double the accepted level of the TARGET2 debts, and approximately 9 times the ECB’s net debt to the system at the end of October 2021 of €352.2 billion.

Any debts connected to the TARGET2 payment system should be included in a member state’s ‘General government gross debt’, but it is uncertain whether they are – either the ones the ECB admits to or the ones that do not see the light of day.

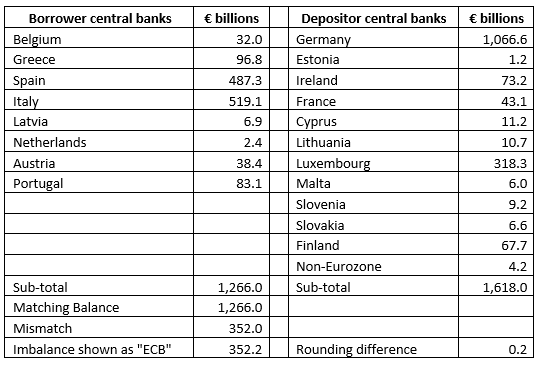

The ECB admits to these individual positions of the central banks towards itself at the end of October 2021:

What are the accepted levels of TARGET2 debts?

It has been accepted by many commentators that Germany is a depositor in TARGET2 in an amount of just above €1 trillion, and that Italy and Spain are borrowers in amounts around €½ trillion each.

These figures, though, are determined after a novation and netting process is applied to the end-of-day balances on the 600 current accounts that are held amongst the ECB and the central banks to process cross-border TARGET2 payments.

The novation and netting kick in during TARGET2’s end-of-day cycle around 18:30 CET and are reversed less than an hour later within TARGET2’s start-of-day cycle for the next-following day. Debits and credits should be passed across the 600 accounts to lend operational substance to the novation and netting, but what these are is not public.

The balances before the novation and netting at the end of October were €3 trillion. The novation and netting reduced them to €1.2 trillion of borrowers and €1.6 trillion of depositors, leaving a net borrower position of €0.4 trillion at the ECB.

This €0.4 trillion is a contingent liability of each member state in line with their central bank’s Capital Key in the ECB, but, being only a contingent liability, it does not appear in ‘General government gross debt’.

It is assumed that the €1.2 trillion of net borrower positions do not appear in the ‘General government gross debt’ of the respective member state, despite their being debts of their central bank to the ECB.

That being the case, the further layer of €1.4 trillion of gross debts – matched by gross deposits – will not appear either. These never see the light of day in the ECB reports. It is unclear, therefore, whether the borrower’s debt is owed to the ECB or to other central banks. Either way, it is a debt of the central bank and should appear in ‘General government gross debt’.

These accounting treatments make a nonsense of the term ‘General government gross debt’.

What needs to be done?

It will no doubt come as an unpleasant surprise to Germany that its net depositor position in TARGET2, huge as it is at €1.1 trillion, could be €2.5 trillion on a gross basis.

Who owes what to whom in total? And during the whole day rather than just for an hour at the end of it? These are the questions that accounts should answer but they do not in this case.

The status quo is not good enough for a matter of such huge importance: the current information gap around the TARGET2 balances is part of the threat to global financial stability presented by the invisible debts bearing upon EU/Eurozone member states.