Published on 30 July 2019 and previously by AccountingCPD.net

There have been several major bankruptcies in the UK recently in which ordinary, unsecured creditors have taken a major loss. These are creditors who have delivered supplies on Open Account. As soon as the delivery is accepted by the Debtor, the Creditor no longer has specific title to the goods: instead they have a claim on a share of the Debtor’s assets, that is on those assets that the Debtor owns, which have not been hypothecated in favour of another creditor, and which are not subject to a preferential claim thanks to the operation of applicable insolvency law.

So what assets will the Creditor have a claim on? Not many, if recent cases prove to be the norm where, firstly, the Debtor turns out not to own the assets that are needed to run its business and, secondly, any assets it does own have been hypothecated.

HMV is a recent case in point. Private Eye (“Eye”) issue 1488 of 25th January 2019 highlighted that HMV’s owner Hilco ”specialises in squeezing profits from distressed retail businesses”. Eye shows how Hilco drew revenues pre-tax out of HMV at several levels – in fees and charges for the usage of assets – and that Hilco “owns other potentially valuable HMV assets, such as the brand and other rights, not part of HMV Retail, the company that died”.

Eye goes on: “HMV was structured by Hilco from the private equity playbook: assets, loans, services in separate companies in parallel Hilco onshore and offshore, UK/US universes”.

The implications are clear:

- Ordinary Trade Creditors were supplying on Open Account into an entity – HMV Retail – which was not creditworthy on an unsecured basis;

- Creditors with the professional ability to assess creditworthiness and run risk themselves had taken security – HMV’s banks;

- Assets (brands, real estate) were held at arm’s-length to their user, HMV Retail, and in companies owned in parallel by Hilco;

- HMV Retail was being charged by these parallel companies for usage of these assets, and these charges were being taken out pre-tax;

- Whatever reports Trade Creditors may have taken from independent credit agencies did not dissuade them from supplying, no doubt because the analysts at those agencies did not understand HMV’s business structure.

The Trade Creditors – who should be near the top of the Creditor Ladder in a liquidation – found themselves at the bottom in practice.

It is easy to be wise after the event in the case of HMV, but how can a trading counterparty protect themselves in advance, if not by taking credit reports? The Orla Kiely fashion company is another case in point. What were the warning signals in the 2017 Annual Report of Kiely Rowan plc, the Debtor to the main bulk of Trade Creditors?

Some signals were obvious. Cashflow was negative by £1.9 million in the year, on sales of £8.3 million. Creditors, at £6.3 million, were three times Shareholders Funds of £2.3 million, and Stocks were £3.9 million – that is 47% of annual sales in a business that was supposed to be Fast Moving Consumer Goods.

These figures painted a gloomy picture at the top level, but it got much worse when the detail was examined, although the notes to the accounts were only lucid to those experienced in reading the tea leaves.

Tangible assets were only £457,780, very low for a company producing £8.3 million of goods per annum, inferring that production facilities were either rented and not owned, or rather owned by shareholders in different companies and rented to the main trading entity, Kiely Rowan plc.

Then we have a lack of any Intangible Assets, like the brand itself or the product designs.

The conundrum of the absence of both Tangible and Intangible assets is resolved by Note 20 on “Transactions with Directors”:

- The directors own the brand name “Orla Kiely” and charged the company £81,989 during the year for its usage;

- £100,535 in rent was owed to D.J.Rowan and O. Kiely trading as Prescott Place Investments for occupation of real estate.

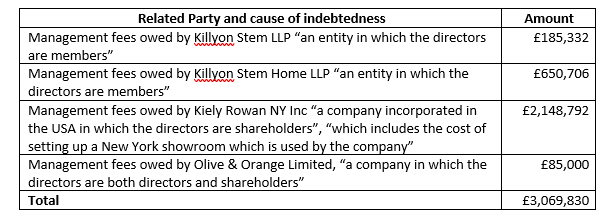

In addition to directly owning the assets that the company needed to run its business and charging the company for their usage, these directors also took substantial salaries of £408,064. Finally we have the portion of Debtors – the largest single asset of the company at year-end – that was “Amounts owed by related party”. Debtors were £4.4 million at year-end, but £3.1 million of this was owed by this “related party”, which turned out, upon reading of Note 21 “Related Party Disclosures”, to be not just one related party but several:

69% of Debtors and 35% of Total Assets (of £8,817,181) were thus in the form of these outstanding balances of “Management fees” owed by arm’s-length companies under the control of Kiely Rowan plc’s directors and owners – and Kiely Rowan plc itself had only £2,371 in cash.

The accounts offer no support for the valuation of these claims, and there are the usual warranties that the valuations were reasonable and prudent, that the audit was unqualified, that the business was a going concern, and that the accounts offered a true and fair view of the state of the company’s affairs, and even that “The company carefully vets potential customers in order to avoid the possibility of significant losses due to bad debts and makes use of facilities with Trade River Finance”, an invoice factoring and discounting company in London.

These facilities do not appear to have been used in the case of the debts owed by related companies, and indeed these amounts were not paid by the Debtors concerned, a major but not sole cause of the ensuing disaster.

Just a year after the directors and the auditor – Harris Trotter LLP – had signed off on accounts attesting to £8.8 million in assets, the company went into administration in October 2018. The Liquidator’s Report showed assets with a realisable value of £67,000 (yes that is sixty seven thousand pounds). The deficit of assets versus claims was £7.4 million, which is 84% of the assets that were supposed to have existed a year earlier.

What can a supplier do?

Firstly assume that all companies are structured like this. Secondly get the accounts of the company you are supplying, and read them: ignore the warranties, and note all the evasions and unanswered questions. Speak to the company about them. If in any doubt, make it plain that it is for the company, its owners and their banks to take the credit risk, so the trading terms should be a cash deposit with the balance payable on delivery, or else a bank Standby Letter of Credit with the same payment timings. Otherwise, as a Creditor, you are taking more risk than the shareholders.