Published on 18th April 2023

Public credit rating agencies have not been even-handed in their treatment of the UK compared to EU member states, given the large shadow debts and contingent liabilities that weigh on the latter.[1]

This is explained in the newly-released book ‘The shadow liabilities of EU Member States, and the threat they pose to global financial stability’, written by Bob Lyddon and published by The Bruges Group.[2]

The labyrinth of EU supranational entities, such as the EU itself, the European Stability Mechanism and the European Investment Bank, has permitted a build-up of debts and guarantees that track back onto the member states but which do not figure in ‘General government gross debt’ – the numerator in the equation Debt-to-Gross Domestic Product that is a prime driver of a country’s credit rating.

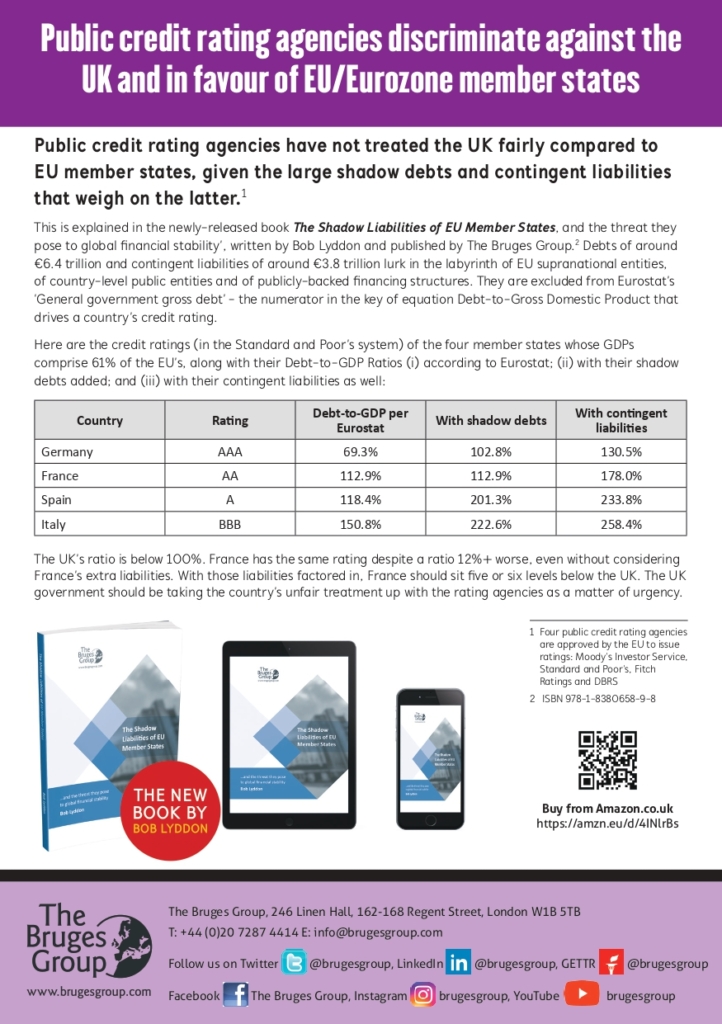

The debts amount to around €6.4 trillion and the contingent liabilities to around €3.8 trillion. The credit ratings (in the Standard and Poor’s system) of the four member states whose GDPs comprise 61% of the EU’s are given in the table below, along with their Debt-to-GDP Ratios (i) according to Eurostat; (ii) with their shadow debts added; and (iii) with their contingent liabilities as well:

| Country | Rating | Debt-to-GDP per Eurostat | With shadow debts | With contingent liabilities |

| Germany | AAA | 69.3% | 102.8% | 130.5% |

| France | AA | 112.9% | 112.9% | 178.0% |

| Spain | A | 118.4% | 201.3% | 233.8% |

| Italy | BBB | 150.8% | 222.6% | 258.4% |

The UK’s ratio is around 100%, and the UK has the same AA rating from Standard and Poor’s as France, despite a ratio 12% lower, even without adding in France extra liabilities.

S&P made a double downgrade of the UK’s rating directly after the Brexit referendum, but did not adjust the rating of the EU, despite the UK being the second largest contributor to the EU budget. S&P re-echoed ‘Project Fear’, referring into alia to:[3]

- ‘a less predictable, stable, and effective policy framework’;

- ‘risks of a marked deterioration of external financing conditions’;

- ‘risk to economic prospects, fiscal and external performance, and the role of sterling as a reserve currency’.

Little of this has materialized but S&P has not even partially reversed its downgrade, for example by raising the UK’s rating to AA+. S&P has not reacted either to the deterioration in the financial status of EU member states, nor to the addition of the debt to be issued for the Coronavirus Recovery Fund. This is inequitable when measured against the treatment of a country like the UK which harbours no supranationals for whose debts it is responsible.

There is a clear basis for doubt as to whether S&P’s treatment, and that of the other agencies, of the UK has been even-handed compared to its treatment of EU member states. The UK government should be taking this issue up with the credit rating agencies.

[1] Four public credit rating agencies are approved by the EU to issue ratings: Moody’s Investor Service, Standard and Poor’s, Fitch Ratings and DBRS

[2] ISBN 978-1-8380658-9-8

[3] https://disclosure.spglobal.com/ratings/en/regulatory/article/-/view/type/HTML/id/1664261 accessed on 13 July 2022