Published on 10 May 2022 and as previously published by irefeurope.org but with more detail behind the numbers

The European Central Bank (ECB) held its latest Governing Council meeting on 14 April 2022 and issued its normal press release.[1] It issued its longer ‘Combined monetary policy decisions and statement’.[2] Finally there was a facile graphic ‘Our monetary policy statement at a glance – April 2022’.[3] Nothing of substance has changed despite inflation being in the region of 7-8%, a development laid at the door of Ukraine and therefore requiring no response.

The pattern is that the ECB only responds when an event provides reinforcement for its stance: in 2020 the Pandemic served to legitimize the ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (the PEPP) and its expansion of Targeted Longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO) as, without them, inflation might have fallen too far below the 2% per annum stated in the ECB’s mandate.

A circumstance that challenges the ECB’s stance is ignored. The ECB claims this stance furnishes it with flexibility: on that basis an eternity of doing nothing leaves all possible actions open, since nothing would ever be tried.

The ECB’s (non-)response to inflation of 5-6% above its target is to lengthen its time horizon for measuring inflation. One hopes this does not mean that, if it can foresee inflation coming down below 2% at the end of that horizon, it will allow itself to do nothing in the meantime. In Cloud Cuckoo Land an ECB with a 10-year horizon could ignore inflation compounding at 8% in years 1 to 9, if it projected inflation of 1.8% in year 10. On Planet Mars an ECB could tolerate damaging inflation of 8% for 5 years as long as equally damaging deflation of 3.8% followed for years 6-10: average inflation would then be on target at 2%.[4] Neither version meets what most people would see as the ECB’s core mandate on Planet Earth: to keep inflation at or below 2% in every single year.

The post-meeting propaganda inferred that the ECB did not understand that these were issues on which it needed to give clarity if it was to retain market confidence. Maybe the ECB is correct – if indeed there is no meaningful financial market outside of the ECB’s own interventions, then the only party needing to be imbued with confidence is the ECB itself.

The ECB’s stance keeps interest rates at a level that deflates the present value of the debts of the Member States, by transferring wealth to them from consumers and businesses in the Member States. Since these are the taxpayers who meet the Member State debt service anyway, it sounds like pointless round-tripping, and a zero-sum game.

Here are the current balances in the ECB’s asset-side programmes:

| Programme | Amount |

| Closed APP programmes | €4.1 billion |

| Covered bonds purchase programme 3 | €296.8 billion |

| Asset-backed securities purchase programme | €27.2 billion |

| Public sector purchase programme | €2,535.8 billion |

| Corporate sector purchase programme | €332.8 billion |

| Pandemic emergency purchase programme | €1,695.7 billion |

| Main refinancing operations | €0.4 billion |

| Longer-term refinancing operations | €2,198.9 billion |

| Total | €7,091.7 billion |

Member State bond yields must remain near zero and to this end the ECB’s open market operations will continue to buy up Member State bonds. While new net purchases into the PEPP will cease, maturing amounts – whatever these are – can be re-invested on the PEPP’s terms. Net purchases into the other four, still-open Asset Purchase Programmes (APP) will re-commence, albeit on their terms, not the PEPP’s: these programmes cannot buy primary market bonds. Limiting the volume of the PEPP’s new purchases might have weakened the support in the primary market for new issues by Member State governments, until one realizes that the ECB Executive can have the PEPP buy the new issues and transfer them into the Public Sector Purchase Programme (which is 80% of APP) as soon as they count as secondary, and without market-testing the transfer price. The ECB can always line up friendly investors like the EIB or the ESM to perform this bridging role if the PEPP is for the time being full.

All this is being done against the backdrop of a compromised system for the quality of the assets being bought, and sole ECB control over the make-up of the PEPP portfolio.

Guideline (EU) 2021/975 prolonged the relaxed credit standards for all Eurosystem operations that were introduced as a temporary measure when the PEPP was established in April 2020.[6] They have now been prolonged twice, this time until 30 June 2022.

Guideline (EU) 2021/174 delegated the power to decide the make-up of the PEPP portfolio to the ECB Executive.[7] The APP make-up must accord with the Capital Keys of the National Central Banks in the ECB. The make-up of the PEPP was originally to be ‘guided’ by the Capital Keys but not to be dictated by them. Now there are no guidelines.

The ECB’s statements make no mention of important issues. If the objective really is Member State debt deflation, who will bear the increasing cost of that and through what mechanism, if inflation has risen to and remains at 8-9% higher than (negative) interest rates?

How do the primary and secondary bond markets continue to operate? Who will want to buy new Member State debt yielding 0% unless they have been assured that the APP will take it off them without a loss? Who would willingly invest in this debt over and above their obligatory holdings? What happens to the bonds of other borrowers, if there are any? Do two parallel markets develop – one of Eurosystem-eligible bonds yielding below 1%, and another of ineligible ones yielding above inflation? Or does the ineligible market get squeezed out of existence?

The ECB’s policies may make Member State debts smaller in real terms but at the risk of embedding a financial system with no relationship to the real world. The Eurosystem gets to own more and more of Member State bond supply, so the pain of receiving sub-market yields falls initially on the Eurosystem itself. They pass it on to the banks via low rates on Minimum Reserves, and the banks pass it on to savers and investors. Minimum Reserve levels on the Eurosystem’s liability-side have to be increased in order to provide the cash to make the bond purchases, and they are remunerated at a negative real interest rate of 8-9% . This creates a major annual drag on the banking systems lending the Eurosystem the largest amounts.

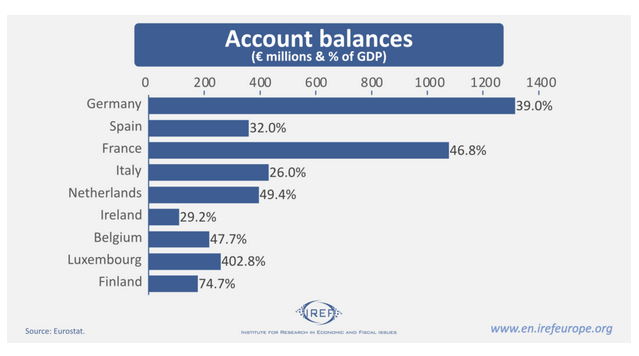

One can already observe this in action in the February 2022 Disaggregated Assets and Liabilities of the Eurosystem. The reference data on population and GDP is Eurostat’s from the end of 2020.[8] This table addresses the nine countries whose banks have the highest levels of current and deposit account balances in the Eurosystem:

| Country | Account balances (€ millions) | LTRO borrowings (€ millions) | Mismatch (€ millions) | Mismatch per capita | Annual drag of Mismatch per capita at 8% | Account balances as % of GDP |

| Germany | 1,315,173 | 421,675 | 893,498 | €10,739 | €859 | 39.0% |

| Spain | 359,373 | 289,689 | 69,684 | €1,473 | €118 | 32.0% |

| France | 1,077,579 | 486,596 | 590,983 | €8,755 | €700 | 46.8% |

| Italy | 430,234 | 453,515 | -23,281 | (€391) | (€31) | 26.0% |

| Netherlands | 395,222 | 173,282 | 221,940 | €12,755 | €1,020 | 49.4% |

| Ireland | 108,805 | 21,048 | 87,757 | €17,910 | €1,433 | 29.2% |

| Belgium | 217,697 | 87,638 | 103,059 | €11,309 | €905 | 47.7% |

| Luxembourg | 258,158 | 28,038 | 230,120 | €383,533 | €30,683 | 402.8% |

| Finland | 176,448 | 36,113 | 140,335 | €25,515 | €2,041 | 74.7% |

The account balances – mainly consisting of banks’ Minimum Reserves – represent a very high percentage of GDP: what purpose do such high reserves serve as regards the operation of the banking system itself? Are the reserve levels not just being set at these levels in order to extract from banks the mass of money through which the ECB can transmit its cross-subsidization policies? The annual drag has the same effect below-the-line as extra taxes above-the-line: it falls on consumers and businesses directly or – in the case of Luxembourg – indirectly through the investment funds in which they hold their savings and pensions.

What kind of financial market is that? It is a covert taxation system, with a primary aim of avoiding a Member State debt default. How does a capitalist or even a social market economy survive with such a parasitical financial system serving only the needs of its public sector?

[1] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2022/html/ecb.mp220414~d1b76520c6.en.html accessed on 15 April 2022

[2] Combined monetary policy decisions and statement – ecb.ds220414~2d6ffb3a83.en

[3] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/visual-mps/2022/html/mopo_statement_explained_april.en.html accessed on 15 April 2022

[4] An amount of 100 compounded at 2% per annum for 10 years becomes 121.90; it becomes 215.89 if compounded at 8%. If it is compounded at 8% for 5 years, it must de-compound at -3.8% per annum for the final 5 years to become 121.90 after 10 years and have compounded on average by 2%

[5] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omo/html/index.en.html accessed on 17 April 2022

[6] CELEX 32021O0975 EN TXT available from https://eur-lex.europa.eu

[7] CELEX 32021D0174 EN TXT available from https://eur-lex.europa.eu

[8] Population data – https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00001/default/table?lang=en accessed on 18 April 2022